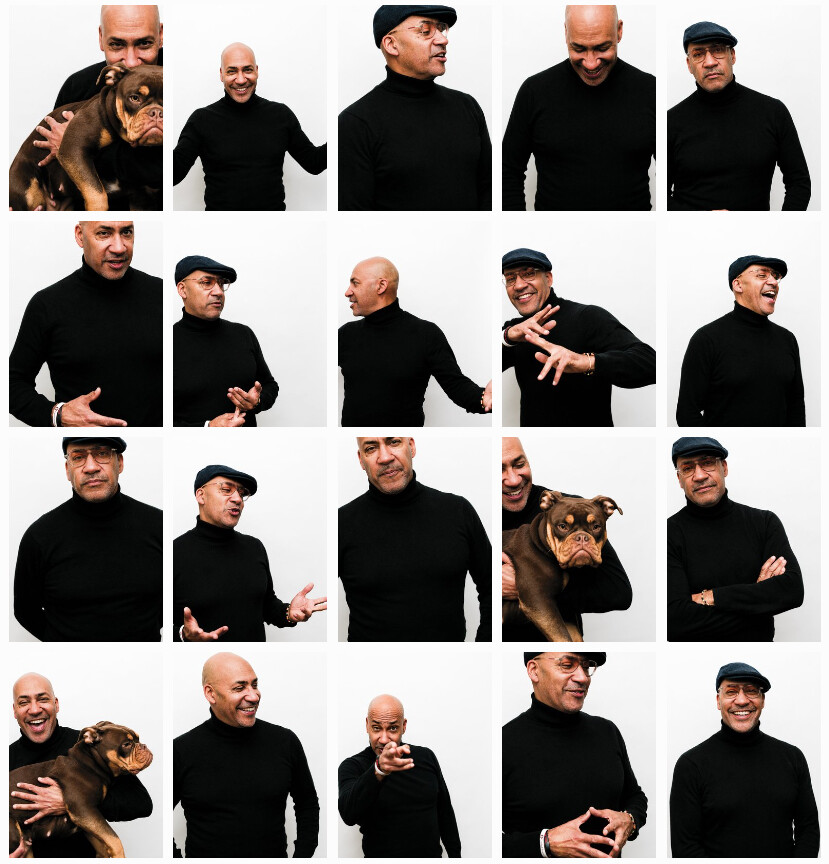

Photos by Michael Piazza

Sheldon Lloyd describes his brother, Glynn, as a visionary—a man who believes a community-based business can serve the city’s neediest and not only survive, but thrive.

In 1994, Glynn Lloyd started City Fresh Foods in a 500-square-foot building in Dudley Square (now known as Nubian Square) with two employees. Today, it is Sheldon who oversees the day-to-day operations of City Fresh Foods, which is housed in an 18,000-square-foot, state-of-the-art food production and distribution center. In 2022, City Fresh won the largest non-construction contract ever awarded to a minority-owned business in Boston to make meals for the kids at Boston Public Schools. With nearly 200 employees, the Roxbury-based business now serves 30,000 meals daily.

Here, Sheldon Lloyd shares the rise of City Fresh Foods and explains its niche in the community. This interview has been edited for clarity and length.

EDIBLE BOSTON: What’s the story behind City Fresh Foods?

LLOYD: My brother saw the opportunity to create access to healthy, fresh food for some of the most vulnerable and poorest people in Boston, while also creating quality jobs and community wealth for people living in Roxbury, Mattapan, Dorchester, Jamaica Plain and other historically marginalized communities.

The company took off when Mayor Menino visited our Dudley Square location and ate our food. Press from his visit prompted a call from the director of a senior service agency. She asked if we could make culturally connected foods for her seniors, meet the senior feeding nutrition requirements and all of the food safety requirements and get the meals delivered on time, ready to be eaten. We took a deep breath and said, “Yes, we can!” And we did.

We started making and delivering Latin meals to seniors around Boston. The business expanded to public feeding programs offered at senior centers, daycare centers, after-school programs, summer camps, charter schools and most recently public schools. At City Fresh, we call this work “community feeding.”

EB: What are the defining moments in City Fresh’s history?

LLOYD: The company’s growth has been and will continue to be driven by increasing demand for healthy, culturally connected, locally made foods.

In 2020, the Covid pandemic helped us see the scope of food insecurity in Massachusetts and more deeply understand our potential to meet critical community needs. With just over 100 employees we were making meals that fed about 10,000 people a day. Then the pandemic hit and the world closed around us. The people we were feeding still needed meals, and every day the number of people who were becoming food insecure grew exponentially. But rather than wringing our hands, we reached out and connected with key community and business leaders.

James Morton, the CEO of the YMCA at the time, provided significant leadership. James grew up hungry and he reminded us that people needed to be fed, and even though we had no funding for the meals, and no idea about how it was all going to work given the scary realities of Covid. Within a few days, the partnership between the YMCA and City Fresh Foods changed from an after-school program into an innovative community partnership to help feed families who were food insecure. Our team simplified our menus and completely changed our operations so that we could double the daily number of meals. We made and delivered 20,000 every day for nearly two years.

Our growth during the pandemic required City Fresh to look for more space, but gentrification and rapidly escalating rents and real estate prices threatened to displace City Fresh from Boston. In 2021, an opportunity arose for City Fresh to purchase a facility at 94 Shirley Street [in Roxbury]. It was a crazy time to consider a real estate project like this—with the cost of building materials escalating at a rapid rate because of inflation, and interest rates rising daily. But with our community partners and key stakeholders, we [were able to] stay and serve the community we love. In 2023, we opened the doors of our permanent home in Roxbury.

The 2022 contract with the Boston Public Schools helped City Fresh Foods win contracts in other communities and in 2023, we became a vended meal partner to Chartwells K–12, the food service provider for the Lynn Public Schools.

We produce over 30,000 meals a day. Our market is about 70% schools, 30% eldercare/other.

City Fresh started with the charter schools. The first wave of charter schools started in the late ‘90s, serving mostly minority students. City Fresh’s menus were packed with the culturally relevant foods the kids were eating at home. City Fresh employees are hired from our community, and they cook the dishes they grew up making. It is immensely important for us to bridge the gap between the people who cook and serve the food in schools and the children from those communities they serve.

EB: What do you feed students?

LLOYD: The Boston Public Schools is a leader in the field of school food and has set the bar high for quality ingredients such as whole foods, humanely raised, antibiotic-free meat and poultry, as well as supporting the purchase of as much locally grown and made ingredients as possible.

We have worked closely to ensure that our menu items meet BPS’s standards and are collecting data on our local food purchasing through the Good Food Purchasing Program.

EB: What is the most popular meal among your younger diners? Your older clients?

LLOYD: Empanadas and Jamaican beef patties are some of the favorites for younger clients. Pastelon (Puerto Rican lasagna) is a fan favorite for elderly clients.

EB: How do you maintain your goal of local and fresh?

LLOYD: We are a high-volume, low-margin food service company serving a vulnerable population with very limited resources, so we must be very careful that we spend every dollar wisely to feed as many people as possible, which sometimes constrains our ability to purchase locally.

We are always looking for the best ingredients that are affordable for our market. While it is very challenging to buy local, as many local vendors can’t meet our volume and/or price requirements, we do as much as we can, with a goal to get to 30% local purchases. We source most of our dairy and bread locally, and buy seasonal, local produce such as apples. We are currently collecting data for the Good Food Purchasing Program to identify areas where we can purchase more local foods going forward. City Growers—now called Urban Farming Institute— was founded by Glynn. We support the work they do to promote urban farming and build resilience in the local food system. We also work with CommonWealth Kitchen, an innovative nonprofit food business incubator that supports diverse, artisan food makers in the Boston area. We think it is important to have and sustain an ecosystem of local growers and producers.

EB: How is City Fresh Foods different from other food catering businesses?

LLOYD: City Fresh competes in institutional markets where the service providers we compete against are almost all large national and international companies. Most of the small and mid-size institutional food service companies like City Fresh have been purchased or have gone out of business.

We are a key part of the local food ecosystem—purchasing locally grown and made food wherever possible and turning it into meals for community members. We are contributing to the resilience of our local food system in a time of climate change.

EB: What about your background?

LLOYD: My awareness of the importance of healthy food and economic opportunity came with my family history in food service. More than 100 years ago, my greatgrandmother, “Great Grans,” left the South. She took the long journey north to Boston to begin a better life as a nanny and a cook for the family that owned the Columbia Gem Meat Company in Dorchester.

My grandfather, Thomas Lloyd, was a man who had many jobs. He grew up in the Jim Crow South. He was a short order cook and the owner of a small grocery in the Everglades. In 1950, the family migrated to Boston in a station wagon using the Green Book. When he arrived, Great Grans got him a job at the Columbia Gem. My grandfather could fix anything, working seven days a week to keep the food production equipment working. His work in several food businesses sustained him and his family.

His son, my dad Weldon, studied hard and was the only child in his family to go to college. He graduated with a PhD in nutritional science.

My parents taught me and my brother important lessons about nutrition. The biggest was balance… eat lots of fruits and vegetables, whole grains, and minimize red meat. Eat chicken, fish and lots and lots of plants. Mind you this was the ’70s into the ‘80s, when the tide was towards processed foods, ever-bigger supermarkets and fast-food chains.

We were a little different, and by the time I left high school my parents were stocking our fridge with skim milk. And my parents are living proof—they are still taking care of me!

My parents also taught us that everyone deserves respect and a chance to put their talents to work. And, like all good parents, they challenged us to put these lessons into practice.

They helped Glynn and me achieve our goals, giving us freedom to do our own thing but also to push and motivate us. I grew up close to my family. I’ve been profoundly changed by the inspiration, insight and love provided by my beloved wife, Ivana, who passed away this summer, and the joy and love of my beautiful children, Mila and Cory. I’m also motivated by those who have built something—James Baldwin, Muhammad Ali and Arthur Ashe.

EB: Is there anything you’d like to share with us?

LLOYD: I’d like to offer three insights from my journey as a change maker, and local food entrepreneur:

All people need healthy food and economic opportunity. This is what I learned from my family.

Real change can happen if you are committed and believe in your mission. This is what I learned from City Fresh.

Finally, food insecurity and economic justice are much bigger than any individual, and we need a community to solve them. This is what I learned from my personal journey and working with community leaders.

We need everyone to create the positive change we are seeking. Please do what you can. Support local, diverse businesses with your food dollars. Support nonprofits working to end food insecurity and to create economic opportunity. Speak up and support public policies that address the underlying causes of food insecurity and economic injustice and add resilience to our food system and equity to our economic system.

This interview appeared in the Spring 2024 issue.

Nina Livingstone is a Boston-based writer who loves eating food as much as she loves writing about it. With the loss of her sight, Nina’s sense of taste has been heightened, and, yes, tomatoes remain at the top of her list. To learn more, visit her website Destination Mirth or contact her at nina@ninalivingstone.com.