How the courage of Anne Frank inspired me and gave me hope after I went deaf and blind.

I was 38 years old when my sight dimmed to darkness and my hearing offered up a mere whistle before it, too, vanished. It happened in a single day. I remember clutching my chest. Fear gripped me. I hyperventilated from the sudden isolation that had enveloped my world.

It was March 2000.

I had no idea at the time that I would grapple with this sudden shift in the course my Usher syndrome had led me on. Usher is a hereditary condition that causes total blindness and deafness, a condition that I was diagnosed with at age 13. Along the way, I had also developed Ménière’s disease, an inner ear disease that causes vertigo, nausea, head noise and deafness.

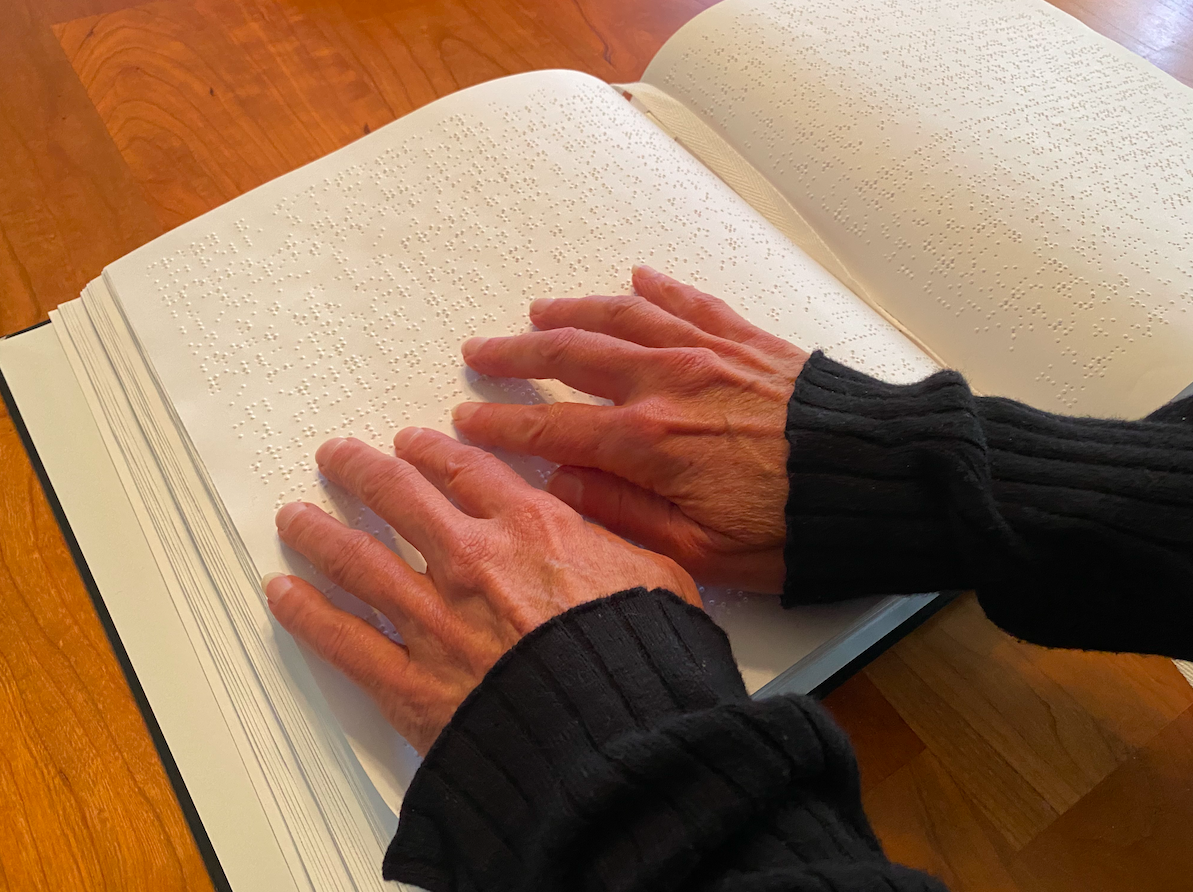

Trapped in this confinement of darkness and silence, the claustrophobia was overwhelming. I groped for the comfort of the only thing I felt I was capable of doing: teaching myself braille.

Hands reading braille

During those 15 months of silence, with the exception of medical appointments to see if I would qualify for a cochlear implant surgery at Mass Eye and Ear, I remained in bed. The Ménière’s and inflammation left me fearful of most foods since their sodium content only aggravated my condition. I eventually lost interest in eating and drank protein liquids to survive.

But it was reading books in braille that truly saved my life. And of the dozens of books I read, it was “The Diary of Anne Frank” that knocked down the wall and tapped into my courage.

I read slowly, as I was never going to be a fast braille reader. I didn’t care. “Anne Frank” was monumental. Why did it speak to me with a clarity that I had not heard when I read it as a child? I imagined myself in the Franks’ shoes. The horrifying sounds of the planes hovering above the roof, the sirens blaring incessantly until a momentary break in battle. The tension of crowding in the small attic together; the despicable secrecy that was forced upon them; the ticking bomb their lives became, their focus narrowed to survival.

I continued to read with accrued respect and spiritual repair. My tribulations were nothing to those of this group of courageous adults and remarkable young people.

When Anne wrote about the sliver of light sliding through a closed curtain of their attic window, I knew I had landed somewhere significant. I had nothing to complain about: my fears, my pain, my suffering were minimal in comparison. Anne had no choice but to stay behind that window. But I realized that I could feel that light; I had a window.

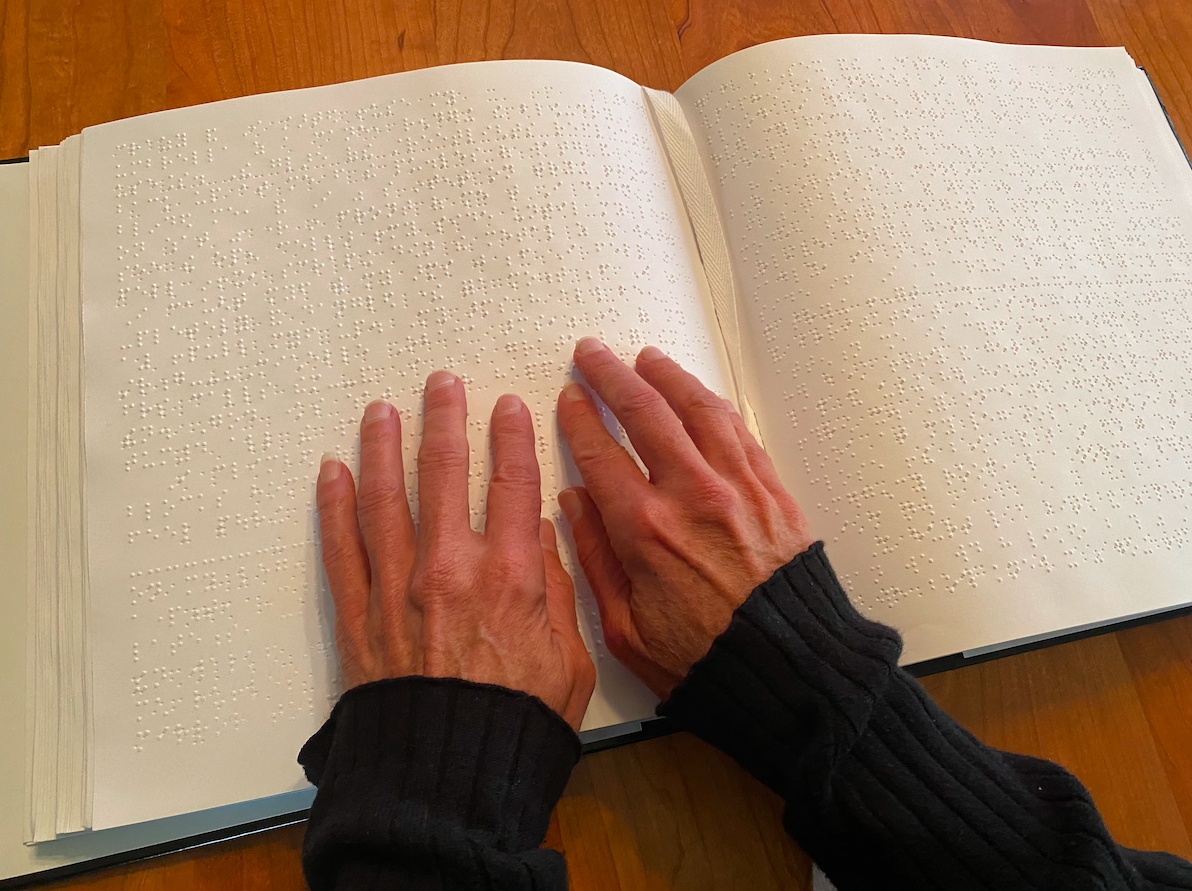

Hands reading braille

I put the open book next to me and started to sob. I just let my heart feel. I didn’t hold back the tears. I simply had to stop believing that my life was unbearable, or that Anne’s level of courage was unreachable. I was still isolated and lonely, but the feeling of being alone lifted. I embraced the book. The reading of these passages and lighting of the first candle of Hanukkah illuminated a jolt of hope that ran through me.

As my housemate, Karen, was preparing for the arrival of her family for the Christmas holiday, I remained immersed in Anne’s life in the attic. The first night of Hanukkah, Karen guided me out of bed and into the dining room. Placing my hand on the shamash, Karen helped me light the candle. I could not see the light as I had in the past, but I was able to feel that glimmer of warmth.

Although I was unable to hear myself when I spoke, I knew Karen could hear me. The vertigo forced me to speak slowly and softly.

Baruch atah Adonai Eloheinu Melech ha-olam, asher kid’shanu b-mitzvotav, v-tzivanu l’hadlik ner shel Hanukkah.

I sat quietly. The previous anxieties and fears dipped and slowly left me. I reached across the linen tablecloth and felt the fresh challah near a plate of latkes and knishes. I felt my fingers touching the rim of a glass, then a plate, and a bowl of matzo ball soup. Struggling with hesitation to eat, I took a deep breath and…suddenly broke into a smile.

“I am grateful,” I whispered.

I found a card with a gift. I knew Karen had labored over the card, making it with a braille labeler. She dialed each printed letter on the labeler, pressing hard with both hands to create a single braille letter. As she moved through the alphabet, the letters from the labeler formed words. She had placed the labels over a traditional card. It read: “Happy Hanukkah, Love, Karen.”

I was moved by the fact she had tried to speak to me in braille.

I opened the gift. It was Art Spiegelman’s “Maus I and II.” It came to be a compelling and moving story about survival. Soon, Karen was reading to me passages from the book, with details of its artwork. She read by finger spelling into my palm. One letter at a time, a slow, tactile form of communication that demanded time and patience, yet provided spontaneous comfort.

I was a young child when my deafness was first discovered. Trips to Mass Eye and Ear were common. It was the onset of night blindness that doubled my visits. I never thought I’d end up visiting Mass Eye and Ear for my vision as well. My experiences have been rewarding with hope for the future in research and the care of others.

As we approach Nov. 28, with a guiding hand I will light the menorah. I will also remember Anne’s courage and the continuous promise to reach outward, beyond my window and into the world. It was a cochlear implant in one ear that truly brought me back, and for that I thank Dr. Joseph Nadol, with much gratitude, love and hope.

“One for each night, they shed a sweet light to remind us of days long ago.”

This article was originally published online on jewishboston.com on November 15th, 2021.