“Judaism does have quite a folklore, mostly from Jewish mysticism, that posits Jewish spirits and even demons,” says Steve Schlozman, an assistant professor of psychiatry at Harvard Medical School and the author of The Zombie Autopsies. “The problem with tying it to Halloween is the less than savory history regarding Halloween and Jewish people, especially during the late Middle Ages and into the renaissance. During this time, at least based on what they taught me in Hebrew school, Jewish folks were often more ruthlessly persecuted than on other days.

“To that end, Halloween posed for me as a child a bit of a conflict. I was told of these issues by my Hebrew school teachers and they ended every class that preceded Halloween with an urgent plea that we not participate in trick-or-treating in recognition of the anti-Semitic history that had in the past characterized the observance of All Hallows Eve.”

We spoke with Schlozman, the Belmont-based author of “The Zombie Autopsies: Secret Notebooks from the Apocalypse,” about Halloween, zombies, horror films and the impact the pandemic is having on children this season.

Q: How did your parents feel about you trick-or-treating?

My family of origin was about as traditional as you could find in the late ’70s and ’80s. We were pretty observant Jews, and I attended Hebrew School until my Bar Mitzvah.

My parents never tried to stop me from trick-or-treating. They understood what I had been told in Hebrew school but they also understood that everybody in my neighborhood [in Kansas City, Kansas] was trick-or-treating and that there was not an ounce of anti-Semitism in the practice. To that end, they wanted me to feel like I could be part of the gang, and Halloween was always fun.

As a guy who loved scary movies, and even recalls with nostalgic giddiness the horror movie book that my grandmother, Bobby, gave me one year for Hanukkah, I never quite worked through my issues with Halloween, but I found myself trick-or-treating, nonetheless. Therefore, it seems to me that the bigger demons on Halloween at least for my generation [of] conservatively raised Jews, are the demons of guilt that are sometimes associated with assimilation.

Q: Can you describe your first Halloween?

I really don’t have a memory of my first Halloween. What I do recall in vivid detail is the first time my parents took me to one of those haunted attractions that spring up around the neighborhood during the October season. I was maybe five or six years old, and they promised us at the door that it would not be too frightening. I remember that simply hearing that it would not be too frightening was enough to scare the hell out of me. I ventured in already quite shaken, and then started crying profusely. My mom had to call ahead and tell people not to scare me and we were ushered through quickly. My sister of course loved this moment. She bravely faced each one of the ghouls in the haunted house and strutted out as the victor in this first initiation of fear.

Q: How did your upbringing coincide with your passion for horror?

I have very clear memories of my father describing for me over and over how frightening Bela Lugosi is in the original Dracula movie. My dad would even imitate Lugosi’s accent and ask me if I could hear the wolves in the distance. Horror films were on Sunday morning on the UHF station from ten to noon and although I was normally a kid who got outdoors as soon as the weather would allow it, I often found myself glued to the set watching those original horror features.

Q: Demons have a place in Jewish folklore as well as the Talmud and Midrash. Where did you learn about these demons and can you tell us more?

I learned a tiny bit about the spirit world of Jewish mysticism in Hebrew School, and then later in a Jewish studies course I took in college. However, I was given a crash course on the subject by the gentleman who collects interesting items for Truman State University in northern Missouri. I was visiting the campus one summer to teach about neurobiology using the conceit of zombies. It was a special program for local kids who were interested in science. The man who ran what was I think the library for the osteopathic medical school told me that he had learned of a Dybbuk through his acquisition of an item that had once belonged to a professor at Truman State. It was this story that inspired Sam Raimi to produce a movie called The Possession. This led me to read more about this usually not talked about part of Jewish folklore. Additionally, I often turn to the opening scene in the Coen brother’s movie A Serious Man. It’s a marvelous short film before the feature begins that displays a deceased man who returns to have a conversation with his family in a Jewish village in the old country. It is both heartbreaking and frightening as well as funny.

Q: The pandemic can be likened to its own horror film, do you see any parallels here?

Heck, yes – and a lot more than I’d like to. There’re the obvious issues – a monster out of nowhere that robs us of our freedom as well as our lives, for example. But perhaps more subtle is the way we personify the virus – we attach political ideologies and even specific pre-existing biases. We forget in its presence how much we have in common and we focus instead on dichotomizing ourselves. There isn’t a horror movie out there where humans do not themselves become the most impressive threat.

Q: Although you celebrated Halloween as a child, was this a common practice in your community?

Absolutely. Everyone was out, and all the usual rituals were observed – trading candy, staying up later than you ought to, watching increasingly scary movies. It was always a great time of year.

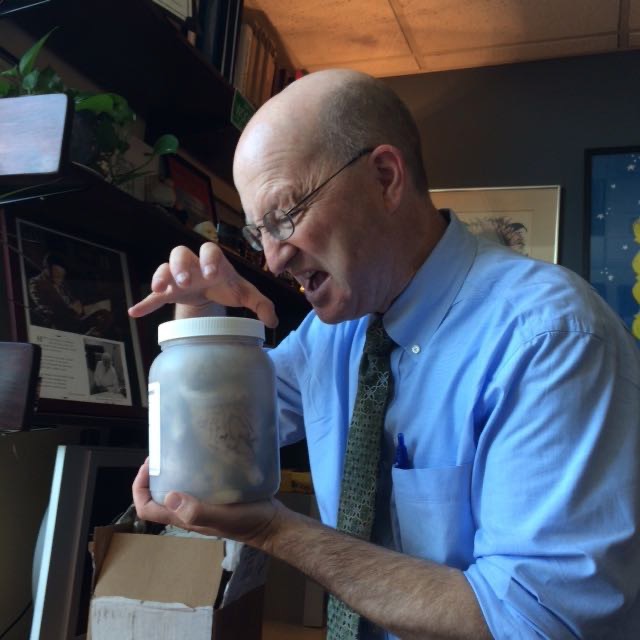

Steve with kids doing a dissection

Q: With Halloween just around the corner and the pandemic still with us, what advice would you give to parents who don’t want their children to celebrate Halloween in a traditional way?

Halloween‘s gonna be tough this year. Part of the fun is the sense of community one sees as younger children in the neighborhood run from house to house and older children transition to hanging out with each other or even staying home to hand out the candy. This year, above all, folks need to remember that times are different because of the pandemic. I know we have a tendency to say just this once we can break some rules, but it doesn’t seem to me to be worth the risk. I would be straightforward with kids, stress that this is an exception to what one usually does on Halloween, consider putting bags of candy separate from one another on the porch for those kids who do come out, and come up with a good family scary film that everyone can tolerate. Make some popcorn, huddle together, and enjoy a Halloween at home as best you can.

There are in fact some seasonal activities that are being kept relatively safe. Outdoor events like corn mazes, as long as folks wear masks and keep their distance, ought to be safe enough. Having said that, I want to encourage people to make their own judgments about what their sense of appropriate risk is, and not to be worried about turning around if things don’t feel as carefully planned as they should be.

Q: I heard you teach film classes focusing on the horror genre at Harvard. Yes?

I do! I teach an undergraduate seminar that focuses on the psychological, cultural and neurobiological aspects of horror films and stories. It feels like cheating to teach this stuff – like a return to my days as an English teacher, but even more in line with my interests.

I also teach the introductory course in psychiatry for a smaller medical school within Harvard Medical School called the Health, Science and Technology Program. This is a joint endeavor with MIT that admits only 30 students a year. Most are MD/PhD candidates and most combine their interests in clinical medicine with careers in some kind of research. Both groups of students keep me honest. I am never as aware of how little I know as when I teach, and I find that feeling genuinely invigorating.

Steve with zombies

Q: Would you call yourself a zombie specialist?

To the extent that zombies aren’t real, then absolutely! I know a ton about the genre, but also, I can kind of make up the science as long as I don’t stray too far from either the fictional or the scientific canon.

Q: Do you have any favorite books that you would recommend on horror?

I really like reading horror to learn about horror. Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein is a must – it teaches the necessity of sympathy for the monster as a means towards understanding one’s own response when things don’t make sense. I love Something Wicked this Way Comes, by Ray Bradbury. Who doesn’t enjoy a lyrical love song to the strained relationship between a father and a soon-to-be adolescent son? For non-fiction, In Cold Blood still gives me chills even to think about.

Q: Which is your favorite horror movie?

Oh, my goodness. I can’t possibly choose a favorite! Lately, I’m very fond of a more recent film called It Follows and another one called The Babadook. These felt like perfect metaphors for some of the issues we face today. Having said that, I enjoyed the heavy-handed political satire of the Purge movies, and I have re-discovered many of the films that Larry Fessenden produced and wrote. His movies always feel fresh to me, filled with sometimes subtle and sometimes not so subtle social commentary, and they never pull their punches.

Finally, I always like to mention the movie Martin. This was one of George Romero‘s early films, and it is a sort of vampire film, but really works best as a strategy. I think that it is maybe the most under-watched wonderful horror film in the horror canon.

Q: When did you first decide you wanted to pursue a career in psychiatry?

I think even before I went to medical school. I didn’t entirely want to be a doctor and was really having a great time teaching high school. Through a combination of parental pressure from my folks as well as my own lingering notion that my personal script (whether written by me, my cultural background or my family’s expectation) required becoming a doctor, I decided to leave teaching (which I loved) and start medical school (which I nearly immediately hated). What I loved most of all were stories, and I happened upon a Dean of Admissions who realized this about me. He assigned me to a rural family practice clinic in Bethel, Vt., where once a week I went to stand by and observe as the old fashioned doctor continued his role as part of his patient’s ever-changing lives. The diseases interested me, but I was more interested in the stories behind the folks with the disease. Psychiatry seemed to match this most closely – an interest in how people navigate their own lives, of where the “ship” can veer off course, and of what we know about how to help to steer it back online.

Cover of The Zombie Autopsies by Steven Schlozman

Q: Your writing and medical knowledge are perfect for turning a zombie into something people can understand … did combining these two areas come naturally and what made you decide to write your first novel, The Zombie Autopsies.

Yes and no. I definitely had been kicking around the idea of making sense of the modern zombie trope through the lens of neuroscience. However, it was the scary year when my wife was undergoing chemotherapy that provoked me to put it down on paper. Because Night of the Living Dead is nearly always on TV, I remember the evening when I tucked my kids into bed, got my wife to sleep after she had received her first or second treatment for breast cancer, and then settled in to watch this old favorite. It occurred to me that I wasn’t going to sleep that night anyhow because of my concerns for my family, so I decided to write a fake medical paper. I thought I needed to leave my wife’s illness to the oncologist and I would have a go at the zombies. My wife’s cancer responded wonderfully to her treatment, and she has been free of any signs of recurrence for nearly 10 years. That’s one of the reasons it’s easier for me to talk these days about the etiology of this strange zombie journey.

Today I live in Belmont, practice outpatient psychiatry and psychotherapy, and happily raise my family. My wife is also a psychiatrist – she specializes in women’s mental health challenges such as postpartum mood disturbances, and she’s a whole lot smarter than me. Our oldest daughter, Sofia, is a Junior at Stanford, and our younger daughter Naomi is in 10th grade. They’re amazing and amazingly different. That’s the fun I suppose in watching your kids grow.

This interview by Nina Livingstone was originally published on JewishBoston.com and can be found here.