Moving from large-format photography into the digital world, she created her own style

By Nina Livingstone

I was in Provincetown on Columbus Day weekend looking for an artist I had heard about … Ilona Royce Smithkin. She was close to 100 years old and was still selling her work from Karilon Gallery on Commercial Street. That is when I discovered Angela Russo — a photographer, an artist, art dealer, and gallery owner.

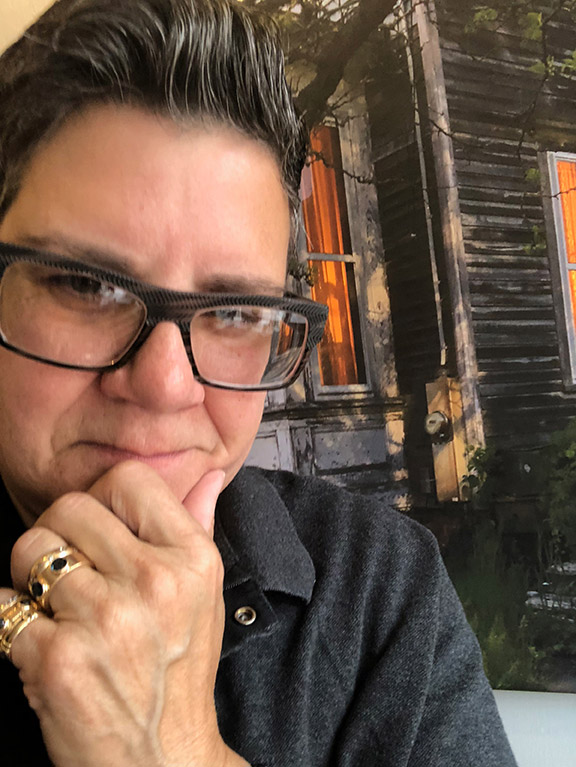

Because I am blind, I asked Angela to describe her work, which sounded original in its execution. My companion assured me it was. I then asked Angela to describe herself. “I am about 5-feet-4 (I was taller). I could lose a few pounds. I am very neat. I have short brown hair with gray in it. I wear very angular glasses. I smile a lot and I love to laugh. I love shoes …”

Then she told me her story and how she went from a high school photography class in 1974 to owning her own South End studio some five years later. The journey was many firsts for a young woman breaking into a male-dominated field.

Q. Do you remember the first photograph you saw — perhaps from your childhood. Can you describe it and what sort of impression it left with you?

A. I do not remember the first photograph that I saw, but I do remember my mother taking pictures of the family early on. It intrigued me, but as I got older, I felt that I might never be very good at the complexities of taking a really great photo.

Q. Can you tell me a little bit about life growing up — suburbs, city, large family?

A. I grew up in a small town in central New York state, Canastota, population 5,000. We lived next to the school, as well as other families who had children around my age. My family consisted of four older brothers, my parents, various cats and a dog named Suzie, that I loved.

As I recall, there was not much I was interested in until I began guitar lessons at the age of 7. By the time I was 10, I was fully entrenched in musical studies, which included sax and piano. My brothers were older, and two had moved out right around the time I turned 8. That was hard for me because my brother Michael, who was 11 years older, was tasked with a good deal of my care because my mother worked.

Michael was also an artist, which I feel greatly influenced me. He made things for me such as a little papier mache’ head named Mister Boscoe that I loved. He also made a tiny replica of our house, which was a mid-century modern home. He was always making things. When he moved away to attend college, it devastated me. He also had his struggles within the family as he personally had not come to terms with “coming out.” He quit school and ran away to New York City. This was a big event in the family, so we all piled into the car and went to see him. What a revelation for me! The big city! That was it! Throughout my adolescence I dreamt about my own move to a big city.

Q. How about your professional education? What was your introduction to professional photography? Can you walk us through your career leading us to your gallery in Provincetown.

A. All through high school I studied music in preparation for music school. In my teen years I was performing solo, playing guitar and singing in local coffeehouses. I also played sax in a rock band.

Then it happened — my true secret dream of becoming a photographer had its start in my last year as a [high school] elective. I had dabbled at it with my first camera being a Polaroid Swinger that only took black-and-white images. I learned most of what I still employ today in high school. That is where I saw my first Edward Steichen, Alfred Stieglitz and Edward Weston images. These works so inspired me. I began to develop my own film.

My eldest brother Joseph, who was an engineer for Kodak, gave me a very good 110 film camera that had adjustments. I learned how to print black-and-white images. Then I borrowed a true adjustable 35mm camera from some friends. I began to experiment with double exposures and alternative processes.

In 1974, right after I graduated high school, I went on a cross-country trip. I took that old Argus C-3 with me and photographed everything! Unfortunately there was no place to process the film I shot, so I just collected it in a bag.

When I got home in the late summer it was time to get ready for college. I decided on Boston. My mother bought me my first real SLR 35mm camera — a Minolta 101.

Still thinking that music was my direction I entered a radio and television school as a recording major because I thought that I could learn how to record myself and also make a living in case my music career did not take off. At the time there weren’t many women in that field on the production side. This made it difficult to connect with my male colleagues. I persevered, but after the first semester I changed my major to Television Directing and Production, feeling that I might have more career options.

The whole time I was still photographing models for the local modeling agencies for pay, to supplement my college expenses. When school ended I had a Directorial Degree and was getting further away from my music life. I got two internships; first at Warner Cable, then at Channel 4 in Boston. Channel 4 went on strike and I was not union; I needed a job! Everywhere that I went I asked, hinted and applied but no luck. I decided to take night courses in photography at two different schools while looking for a job.

Moving into a man’s world

Then one day I went into a camera store called Stone Camera on Bromfield Street in Boston. Minutes after a very discouraging interview to try to become a file clerk, I asked one of the men where their photo chemicals were. I told him that I had arrived from a cross-country trip and wanted to develop my bag of film. He seemed nice and was very interested in what I knew as far as processing. I told him that I was making some income photographing models, but also hinted that I needed a permanent job. He said that he would ask the other male employees if that would be alright because a woman had never worked in that business in Boston before. That was in 1976.

Bromfield Street had a history of up to 10 photographic stores at one time even though it was only a city block long! The next day he called and told me that I was hired! That was the beginning of a very difficult but productive road. I had to earn the respect of the other male employees and the mostly male clientele. I took the challenge on and made it a point to become very proficient in all types of film formats as well as processing and printing methods. After a year of the struggle of cleaning the whole store and also stocking and selling, I was promoted to manager!

Exposure, expansion, and equipment

About that time, 1977, I heard that Gay Community News [GCN] was looking for a features photographer. I really wanted to be a more engaged part of the community, so I shot a test for them and they hired me! This was great because I could go to events at night and meet all kinds of people and performers from all over the gay community and country. I would shoot and print contact sheets of my images with a very short deadline. I didn’t make much, but I began to get a reputation for knowing my stuff and even had a nickname, “Flash,” for my expertise at capturing images with flash that others had trouble capturing!

I was not “out” to my employers, particularly the camera dealer who owned two stores at either end of Bromfield Street. I published my work with a pseudonym, Noelle Grays. GCN was on that same street in the middle of them! I would make my deliveries telling my workmates that I was going to get a coffee. Then I would run there to make my deadlines.

All the while I knew that there was more that I wanted to do in my pursuit of a photographic career. Then, in 1978, I met a very famous advertising photographer who was a client of the store. We became friends and after a while I asked if he would take me on as an assistant. I told him that I would even work for free in order to progress. He hired me and paid me! Sometimes he would let me book models for my own shoots at night in his studio so I could make extra money and learn about more lighting and sets.

A couple of the models I photographed had friends who had heard of a freelance photography job opening up at Filene’s. I found out what they were looking for and borrowed $3,000 to buy the equipment I needed for a test shoot. It worked and they hired me! In the beginning I would travel on the train from Orient Heights in East Boston with all of my equipment, which included a very big and heavy 4×5 camera to shoot mostly at night. I also kept my sales job on the weekends.

Right around that time I left the assistantship because the photographer I worked for could be very difficult. He would make me clean a 3,000-square-foot studio, print and process all of his black-and-white film, and drag all of his equipment around. He was a perfectionist.

In 1978, a beautiful studio in the South End of Boston became available, and even though I didn’t know how I would be able to handle the high rent, I took it. I struggled to keep it, but it made it possible for me to expand and get my own accounts because now I had my own full studio and darkroom. I was also able to live there in another part of the space.

Famous clients, changing ways

I started to get clients like Lacoste, Clinique, and Waterford! I was really on my way, I was starting to make great money and I was able to pay for my first few pieces of equipment. Then the photographer I worked for killed himself! All along I had kept my dealership job part time, so after his family got over the shock, I asked his estate lawyer if I could make a bid on his equipment via the store I worked for. They said yes, and that helped me get the professional equipment that I so desperately needed.

I then started the process over the next 20 years of repairing that equipment piece by piece because even though it helped me get started, every piece that he owned was in disrepair.

Then within a year of renting my space, the building was purchased by a developer and was slated to go condo. This meant buy the space or move. I had been making money, but no bank would give a freelance photographer at 22 years old a note. I had to have a co-signer, and at 28 percent interest no less! I got a co-signer and I got the loan! The space is the same one I am in now after 40 years!

My career was off to a great start, and through the years I had some wonderful clients and made many friends.

Serious injury and starting over

My advertising photography career rolled along until about the mid-nineties, with the advent of digital imaging. During that time I had my ups and downs. Flooding in my building caused me to almost lose all of the equipment it had taken me years to collect and repair. Nevertheless I persevered and built my equipment back up. I was not going to quit, but professional photography was changing. I could see that the use of large-format film, which is how I made my living, was in decline and that I had better go back to school and “embrace” digital imaging. So there I was, back in school from 1995-97 with 20-year-olds and not very happy about it.

After a long career shooting for the likes of Burberry’s, Lacoste, and Waterford, I went full steam ahead learning digital imaging. I needed a job while this was going on, so I got one managing a pro photography store. Within a few months of working there, I fell off a loading dock and needed surgery. It was 1999 and there I was, stuck in the apartment recuperating.

Not being the type of person that is a victim, I decided to hone my digital computer skills on my personal images that I had been photographing the whole time that I was shooting professionally. I found eBay at that time and proceeded to sell off my unused camera equipment. This money was then reinvested into the equipment I now needed. I started to scan my images via high-resolution scanners and began printing on the large-format printers I had purchased. My recuperation was a long one, and I just focused on my personal work. I worked on my health and did many months of physical therapy.

Then, in 2002, my mother died. This was a very difficult period for me because we were very close and she was my biggest fan.

Over the years I had saved a little money and wanted to try to buy the family home in Canastota. I tried to negotiate with my four brothers, but it was not going well. Then [my partner] Sandy had a dream that my mother was angry and did not want me to buy the house and that my brothers were fighting over money. I heard her message and stopped trying to buy it.

During this time I joined “South End United Artists,” which put on art shows in my Boston neighborhood. I started to see that what I had been making was well received. I sold a few pieces, but I had no real plan of how to go forward, and those shows were only a few times a year.

Another chapter

Four years after my accident, a friend called to invite Sandy and me to Provincetown. Once there he said that he wanted to show me a house that he was thinking of buying. I knew the 1740 house and told him that it was very expensive and needed everything! He said, “If you think this house is a dump then look at the one next door because it’s for sale too.” We looked in the back door and could see that it needed a lot of work but it had good bones. A week later I had made a low bid on it thinking the owners would never except it. They accepted my bid! I think my mother sent me there!

We started to work on it on weekends, and I moved a printer there and started to make my work. I would make it on canvas and would varnish it on my back fence and leave it to dry. Occasionally we would have strangers roaming around my yard inquiring to purchase the work. At this point I had no real plans to sell the work and was just trying to make pieces for the house and possible Boston shows. After a year or so of people wanting to buy the work, I got the message and decided to look for a shared gallery space. Most of the artists that wanted to do that really just wanted me to sell their work while supplementing their rent. Then, in 2005, I heard that two women were looking for a third person. I made an appointment and met with them. One was an impressionist painter in her 80s and the other was a watercolorist and a retired judge.

They didn’t know what to make of my work because they hadn’t seen anything like it before, but we liked each other and made an agreement. It was 2005.

Brain cancer? A miracle instead

Provincetown is the oldest art colony in America and the birthplace of impressionism in the United States, but not a center for photographic work. I moved in and proceeded to set up and right away started selling my work as well as theirs. It was amazing! I could see that things were definitely moving in a positive direction. Over time, my work started to go all over the U.S. and the world! At first I could hardly believe it!

Then in the summer season of 2008 I began having terrible headaches. I called three doctors who knew my history and none of them were neurologists, so they didn’t end up examining me. The headaches increased, and finally I called a nurse practitioner I knew and told her my symptoms.

The next day I had a CT scan done. A few days later when the results were finally in, I received a call from the doctor, and he told me that I had a metastatic brain tumor! He connected me with the head of neurology at Brigham and Women’s Hospital. He looked at my tests and thankfully decided not to biopsy my head. I went in for surgery and asked them to please not shave my head. I woke up with all of my hair, and as it turns out it was not brain cancer but a leaking aneurysm! Five days later I was sent home and entered into the record books for my mistaken prognosis!

Within a few months of recovery I came out with a book of my Cape images and had an event around that. The next spring I reopened the gallery. The three of us continued until the retired judge decided that she wanted to do other things. Then it was up to me to continue. I decided to try to represent other artists. I was considering asking a world-class male figurative painter to show in the gallery. He accepted and we sell many [of his] pieces — which brings me up to today.

Q. Isn’t there still a need for large-format product photography? What happened within the industry that made you change your style or path?

A. There is limited need for large format in that field of advertising. My direction changed organically, and now that it has, I welcome this change because I am paid for work I have made of my choosing. This is antithetical to how I worked in the past.

Q. Do you find digital easier to work with now?

A. In the beginning of my experience learning digital imaging I did not feel that the quality was as good as a 4-inch by 5-inch negative or transparency. High quality is more achievable today, but the prohibitive cost of true high-resolution camera equipment is meant for only a few. There is a disconnect between the false notion that high-quality, hig-resolution pictures can exist in a point-and-shoot model. The reality that a common cell phone image — with its limitations — is printable in large proportions [isn’t accurate]. When viewing an image no bigger than a few inches, an amateur feels accomplished. The actual skill one requires to make a high-quality, high-resolution image with aperture and shutter settings that can be printed in any size is still very necessary today. This is what I have devoted my life to. There is no [substitute] for training and skill.

Q. I am told that your “Modern Images” look like paintings. Can you describe the process without giving away too many trade secrets?

A. I work in five styles whether on paper or canvas, all of which I produce in a very painstaking and focused manner. I do not use the term Giclee, which only means “to spray ink”; it does not refer to the quality of the ink. As with any other process, there are different types or qualities. Dye ink has an image life span of five to seven years, and the color starts to shift after the first year. This is mostly what you would receive if you upload an image to a web site to be printed.

The other main type, pigment ink, has many brands and types but is still again better than dye ink.

What I employ is pigment ink of the finest and widest color range available that is also extremely stable. There are no shortcuts for me. I then, in the case of canvas, varnish with an equally high quality coating that I apply twice for added lightfastness. Any slip-up in the process will produce inferior quality. This kind of high quality is what I stake my reputation on. It has taken me years to produce what I take pride in showing and selling today.

Q. What do you envision happening in the world of photography a decade from now? People wanting to return to film cameras? Similar to people buying turntables and vinyl to augment CDs and streaming?

A. Film in some cases has never left any legitimate photographer’s consciousness, and is having a similar resurgence among amateur photographers who are now buying up used cameras they could not afford in the past. Kodak has once again begun making Ektachrome transparency film. However, the real issue is securing quality processing. This is the problem. Along with any kind of processing there is another even more serious consequence of that processing: the environment and pollution of ground water. I virtually all but stopped because as an advertising photographer in the ’90s the EPA once yearly would send me a very large official form that I was required to fill out in reference to the safe disposal of chemicals. I got the message. What I use today is aqueous based aside from the varnish.

Q. Your black-and-white images are described to me as very stylized. As if you printed them from negatives in a darkroom. (Description: grainy, blurred, similar to what a Holga might produce.) Is this a vote to return to simplicity?

A. I have in many cases utilized high resolution scans and printed from them to keep a true black- and-white quality. I have also been able, after much trial and error, to achieve a similar result from some esoteric papers.

Q. You also have a section on your website you call “old-fashioned cars.” What’s the fascination?

A. I love old mid-20th-century cars. I am mid-20th century. I grew up in a household with four older brothers who loved that era of cars, and I suppose I inherited that love. Actually I even own a 1950 Cadillac that took 20 years to restore. The style and those rounded and darting shapes of fins and fenders will never be again in history. I love the way they look and feel that they are a true art form.

Q. From your Cape Cod collection, what scenes are the biggest sellers? What do you consider a highlight in your professional career?

A. Some of the images that I have found popular are the watery scenes of the bay, the wonderful Provincetown sunrises and sunsets. I have been interviewed by NPR for the foggy, misty ones of Beach Point in Truro and the Cottages, which are very popular. Also, I had the honor of my image — a shot taken at 1 a.m. of the Moors on a moonless night — being chosen as the cover photo for “Wetlands, Our Common Wealth.” Also my image of the neon “Lobster Pot” sign was nationally published on the cover of Traditional Home magazine and remains a favorite. Let’s not forget my picture of “Pearl,” my 1950 Cadillac at Herring Cove at sunset!

Q. What about your low point?

A. One of my low points was losing a main computer and all of my associated images on it last year when it crashed. They were backed up but not sized and saved as I had them arranged on the computer.

Q. You have Arianna Huffington listed on your Linked In page under Interests. Why Arianna?

A. Arianna Huffington is a brilliant force of nature and a great example of what women can do when faced with different adversities. Making a difference in her life by telling stories and giving a voice to all sorts of people, but particularly women, makes me admire how hard she worked to make her dreams happen.

Q. As a blind writer who, when I had sight, was both a photographer and videographer, I’d like to ask you to describe your favorite pieces to me.

A. Some of my favorite pieces are the foggy, misty seaside images that require skill and timing to capture. One of my personal favorites is called “Blue Fog Marsh.” I remember where I was and what I had to do to get it, so I guess you could say I feel that images like that are great achievements in my career.

Q. Is Provincetown a creative muse for you, or do you shoot as actively in Boston?

A. Provincetown is a creative muse for a lot of us in that community. Even though I have a full studio dedicated to my work in Boston and much more room to make my work, I am far more productive in Provincetown. It is a very beautiful, natural environment. Because of the location, the light that is reflective and refractive is like no other place. I feel that the work I am able to produce is endless. This is evidenced by the five different styles that I have created over the years since my work began there.

This interview was edited for length and clarity. You can read my companion piece on Angela Russo in Boston Spirit Magazine, which can be found at: Club Café , 209 Columbus Ave., South End Boston; and Cathedral Station, 1222 Washington St., Boston. To read an online version of Angela’s story, visit Thrive Global https://thriveglobal.com/authors/nina-livingstone/.

Nina Livingstone is a Boston-based writer who has written for Edible Boston magazine, Portland Monthly magazine, and the Harvard University Gazette, among others.