By Nina Livingstone

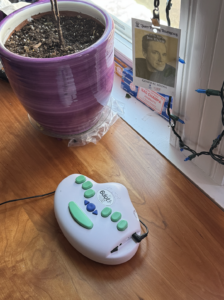

It’s been almost 10 years since I was at the Carroll Center for the Blind’s Technology Fair and stopped by the LoganTech table. That’s where I first saw the 6Dot Electronic Braille Label Maker. I was fascinated by it. For several years I had been using the Dymo tape with the plastic manual braille labeler. You had to press so hard; you could get arthritis in no time! I remember sighted people trying the manual braille labeler as they could type real notes from it. The regular letters on the labeler matched with braille letters. Unfortunately, they, too, found it excruciatingly difficult and tough on the wrist and hand! So when I came upon the 6Dot I was obsessed. It was so smooth and electric! I knew I had to get one.

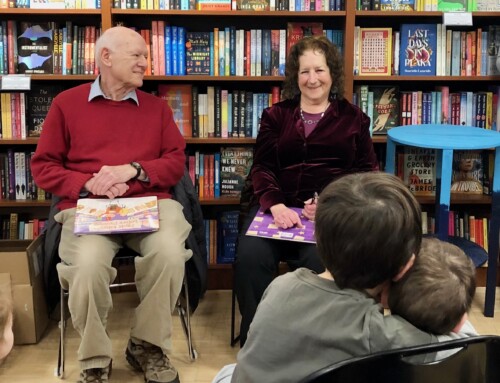

In this edited interview, I speak with LoganTech President and CEO Glen Dobbs about the technology his company has introduced and the story behind it all.

LoganTech 6Dot Electronic Braille Label Maker

NINA LIVINGSTONE: The 6Dot Electronic Braille Label Maker is a wonderful device. Who designed it?

GLEN DOBBS: [In 2009] Karina Pikhart, who was a Massachusetts Institute of Technology mechanical engineering student, designed it. It was a class project where they had to create a device to solve a societal problem. The students had done some research and determined … there was no good braille label maker. So they decided to develop one.

It started at MIT then wound up at Stanford University at their business incubator. I stumbled on them at California State University, Northridge.

I had invented the BrailleCoach [a talking braille learning system] and we were looking to augment it. I met Karina when she was displaying the braille label maker, and I was like, “This is amazing. Can I resell these?” They had only made 200 of them, and they were sort of done making them, and they were trying to figure out what their next step was, and I wound up acquiring the company.

LIVINGSTONE: That was before LoganTech?

DOBBS: Yes. Do you know the story behind LoganTech? It’s a very unusual thing. My son (Logan) has severe autism, and he can’t talk. I was working at a company developing access control technology for buildings, and they have proximity cards, which open up doors in buildings, like a hotel room — that’s a proximity card.

My son is sighted, and he would use movable picture books. We would use these pictures to communicate, and he would hand you the picture of McDonald’s, and I would say, “Oh, you want to go to McDonald’s?” So we decided to make the proximity cards talk and we made a talking machine that would take the pictures and turn them into speech.

And then people kept saying that you could put braille on this device to teach braille. So we decided to make a thing called the BrailleCoach (Talking Braille Learning System), which uses the RFID (Radio Frequency Identification) tags that have braille on them, and when you feel the braille, and then you play it on the machine, it tells you what the dots are. So it’s for learning braille. And that led to wanting to make the label maker.

But in the meantime our speech therapists were using the Logan ProxTalker with tactile symbols for nonverbal blind kids. These were kids who couldn’t talk, had autism and also couldn’t see but they could feel what was on the tag and then play the sound. So they’re able to use this device to speak. We wound up putting braille labels on those tags — introducing those kids to braille literacy. So it’s a very interesting hybrid of one direction going to another.

LIVINGSTONE: With 1.3 million legally blind people in the U.S., of which less than 10 percent read and write braille, where’s the trend going? Away from braille?

DOBBS: From what I’ve learned, the No 1 cause of blindness is premature births and the lack of correct post-birth treatment. That problem has been virtually eliminated in the United States and Europe. In other countries, where they don’t have the medical care, blindness is still prevalent. People who are blind in the United States often have issues in addition to blindness, so they have a more profound disability, cortical visual impairment, and so forth. That’s one reason. The other reason is that many of the blind people have gone blind later in life [because of] macular degeneration.

I have a friend who is blind due to a motorcycle accident. His skull [and brain] swelled and it pinched off his optic nerve, and he became blind and paraplegic. I showed him the BrailleCoach, and he said, “Well, if I wanted to learn braille, I would use the BrailleCoach, but I don’t need to learn braille because I already know how to read, and I can use audio devices.”

So I’ve seen a wide range of people and it’s really a matter of where you live and what situation you live in.

LIVINGSTONE: In my case, I am blind, and I am deaf in one ear and have a cochlear implant in the other. When I do interviews with people, I usually have everything translated into braille and depend on braille for accuracy of the quotes. Braille has become such a dependent way for me that I use it daily with the computer and the braille display and the braille labeler. I also use my Perkins Brailler to take down notes and ideas. It’s all very effective and it really helps with work, efficiency and productivity, and so forth.

When I saw the LoganTech labeler, I was blown away. It made me think of others who could use it. I told my sister and brother, both have the same thing I have, Usher syndrome, and they said, “Well, where did you get it? How can I get one?” There are a lot of people out there, who I think, should know about this.

DOBBS: You’re absolutely right, I mean, I think, for the people who go blind earlier in life, braille is the only way to literacy, and I think literacy is an educational right. It’s a necessity for education. The people that already were literate and go blind later in life, you know, in their 50s, 60s, it’s a different story. But it would be unethical not to teach a kid braille or anyone who is school bound early in life.

One of the things I hear, and this bothers me so much because my son has severe autism, and he can’t talk, and he is not able to read and write. But I hear a lot of times they’ll say, “Here’s a kid who has autism. He’s blind, nonverbal, and he’ll never learn braille.” And I completely disagree. I think those kids need to be exposed to braille. Whether or not they read, they might do what I would call “sight reading” — they would recognize the word and associate that with a tactile symbol. They would know “this means that” as they’re learning, and I think it’s important to expose those kids just like they do kids who are sighted with autism. They put words below the pictures. They should do the same thing with the kids that are in this situation.

LIVINGSTONE: What would you like to add?

DOBBS: One of the things that always surprises me about the things that we make is the unique ways that people use them. The braille label maker for example, some people like to write down phone numbers when they meet somebody. You can label your medications. You can label your food items so you can tell if it’s cat food or tuna fish. We have building inspectors who buy them to label the room numbers on buildings because they can’t get a certificate of occupancy without braille labels. We have museums that are putting them on the signage to tell people what they are looking at.

And the BrailleCoach was really intended for people who are living remotely or don’t live in the country where they have access to a blind school or have a teacher for the visually impaired — or very limited access. Also for people who go blind later in life, or are curious, and would like to learn braille. Also people with other disabilities, cognitive disabilities where it’s actually a big help to have that self-teaching tool to augment the time with the teacher.

Special thanks to the LoganTech Team: Kelly Longo, customer service, and Gustavo Toral, sales manager.

LIVINGSTONE: One last question, do you have any other projects in the future?

DOBBS: Yeah, we are actually working on an improvement, a couple of ideas we have in the label maker to make it integrate. It’s more of a teaching tool where it would tell you what you typed. Also we want to turn it into a device that can be used as a printer from a computer. Printers for computers do exist, but there aren’t good label printers for computers.

LoganTech is located in Waterbury, Connecticut. To learn more, visit their website at www.logantech.com or call (866) 962-0966.