By Nina Livingstone

Photos By Elaine Hiller

Bundled up against a biting wind, I stood in front of Mei Mei’s wall of windows. I couldn’t wait to get inside. Irene Li had described her restaurant as warm, cozy, and comfortable. With its bright-yellow chairs, exposed brick, and wooden-topped tables, it was indeed inviting.

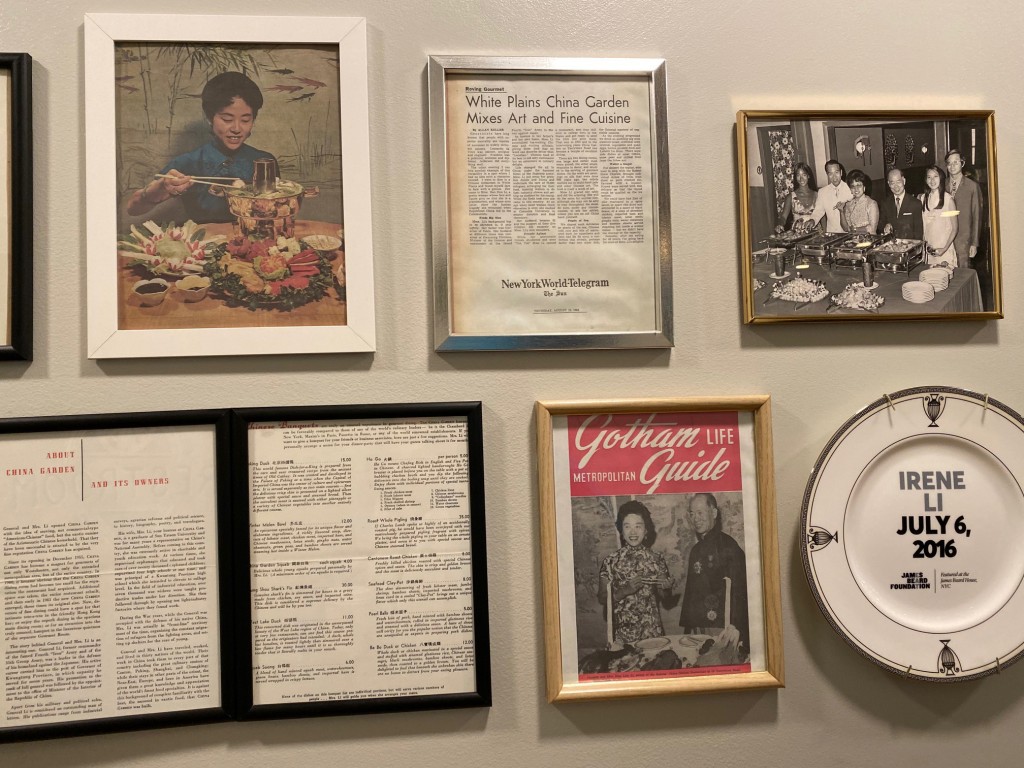

Once inside, I realized it was the open-kitchen concept that allowed the aromas to drift out, unrestricted. Stools lined the counter and natural light (or as much as a winter’s sky could eke out) filled the Boston eatery. A hallway laden with awards, framed articles and photos of grandparents, parents, and siblings; shelves with locally sourced sauces and syrups shared space with family cookbooks. It was clear that Mei Mei straddled several worlds, embracing the urban and quirky with a mom-and-pop ethos. It is what owner Irene Li describes as a template for the future of restaurants.

Li’s step into the future doesn’t stop there, however. With trained knowledge on how to make customers with disabilities feel welcome, Li worked with my blindness by touching my arm and pointing my hand toward everything she was describing. With my hearing impairment, she was gracious when repeating her answers.

EDIBLE BOSTON: What is the story behind Mei Mei?

IRENE LI: The story of our family—Chinese American, living in Brookline, totally obsessed with all kinds of food. We grew up eating Chinese food at home, and also everything else Boston had to offer, including pizza, grilled cheese, mozzarella sticks … That’s why we sometimes call our cuisine “Chinese food with cheese.” The idea for our business came when our brother, Andrew, who had been working in hospitality for almost a decade, saw the food truck trend taking off. He called my sister and me and asked if we might be interested in jumping on the bandwagon with him. We agreed but insisted that he name the business after us, his “mei meis,” Mandarin for little sister. Our approach to food has always been about ingredient quality, transparency, and personality.

I hate calling our food “fusion”—sounds like it came from a laboratory—because to me, it’s much more organic. It’s the natural, multicultural product of growing up in an immigrant family in the U.S. And it’s always been about imbuing our food with lots of personality, fun and love. We opened the restaurant in 2013, dabbled in shipping container [farms] and sauce lines, published our cookbook, and are now looking at the next steps. In the last two years, I’ve taken over operations as my brother and sister have moved on to new projects (like having kids!) and the team has grown into new roles with me.

You’ve been nominated five times for a James Beard Rising Star Award … which is an honor right there. What feelings do you have attached to this?

Every year I get slightly nauseous when I see my name on that list. I also have a lot of questions. Like, do they know I learned to cook by watching YouTube? That I have no culinary pedigree, no award-winning mentor? That I have no PR firm that handles headshot requests? That I’ve only done so much while under 30 because my brother and sister went against all reason by entrusting me with so many parts of our business? I try not to think too much about awards, but they’re part of life in this industry and I know that winning would have a hugely positive impact on our team and our business. So this year, I’m feeling pretty determined to figure out how to win, or at least to break the finalist list. It’s my last year of eligibility for this award, so I’m feeling a little pressure in that sense. I don’t think that what’s landed me on the Rising Star list will get me on the Best Chef Northeast list, so it kind of feels like my last chance. And I think that compared to 2014, when I got the first nomination, I’ve come so far and accomplished so much. So it almost feels like—if I were ever deserving in the first place (which I still question), I’m even more deserving now. Not as a matter of ego—just as a matter of five years passing.

Your interests embrace a myriad of elements: eliminating food waste, open-book management, serving the community, providing a safe dining experience for all, gender-inclusive staff training … to name a few. How do you bring it together?

All our values at Mei Mei, while they may seem disparate, are the product of a central goal: to make Mei Mei a business that people are proud to support and proud to work for. I think that in the restaurant industry, we focus too much on just the food that restaurants offer [and] under-emphasize how important it is to work for a company you believe in, whose practices you are proud of.

For a long time, I knew that there were a lot of people in the industry who I thought were awesome chefs, great people, but I would NEVER consider working for them. It was about more than just loving their food. I had a few “aha moments” in the last couple years when we started adjusting some of our practices—buying more conventional produce, doing a little bit less composting, for example—and our team let me know that it felt bad to them. It was amazing to know that they cared as much as I did about the choices we made. So, I’ve intensified my efforts to do things—advocate for certain issues, change protocols, make statements—that show our staff that we share the same values. Hopefully that flows to our guests as well.

Which of these do you believe holds the key to a successful restaurant?

It’s hard to choose one thing, but anything that concerns our staff is always going to be key. The concept of internal hospitality dictates that if you don’t take care of your staff, they can’t take care of your guests. I also think of it in terms of Maslow’s hierarchy of needs—if they come to work hungry, if they feel physically unsafe, financially strapped, not cared for, how am I supposed to demand that they be caring, generous, creative and growth-oriented? So, we focus on not only meeting their basic needs, through access to groceries and contributions to health insurance, but also their desire for recognition, belonging … “an abundance mentality.” The restaurant industry is notorious for demanding sacrifice. I don’t want my staff to feel like they shortchanged themselves to come work for me. One small example is that we close for all major holidays and often for the days before and/or after. I remember never seeing my brother on Christmas. It’s not worth it to me to ask that of our team’s families.

You’ve mentioned sustainable practices, including composting. How much compost do you produce at Mei Mei and where does it go?

We produce about 60 gallons of compost per week and it gets picked up by CERO and composted on local and regional farms. When I learned that most compost gets incinerated or anaerobically digested for fuel, I was a little surprised. So working with CERO was exciting because it actually represented the closed loop that many of us think of in connection with composting.

How and why have your views shifted over the past years as a chef, both politically and personally?

When we opened, I was most interested in local sourcing and environmental justice as opportunities for change in our industry. These days, I’m a lot more focused on workers’ rights and empowerment. I see these things as intertwined, of course, but I feel like the latter is a bigger, more interesting problem to address, and is key to the survival of cool, offbeat mom-and-pop restaurants. On all issues, I’ve also become a lot more vocal through my writing for WBUR, through our social media and through the causes we choose to support. I’m choosing to spend a lot more time working with nonprofit organizations in more structured, enduring ways (board memberships, formal mentoring), rather than just participating in fundraisers. I grew up in a family that always met my needs and supported my dreams, and in recent years I’ve come to know that this privilege is, firstly, real and with real impacts, and secondly, nothing to be ashamed of or awkward about as long as I don’t squander it. So, it’s my responsibility to do more than just operate a nice restaurant.

Do you feel your background has prepared you for both—the creative aspects of cooking and maintaining a successful restaurant?

In school, I was always interested in issues of identity and social equity. For a while it seemed like food was a departure from that, but recently it feels like I’ve come full circle. I never had any inkling that I’d end up working in food, but it’s starting to make sense, at least in retrospect.

You have a reputation for ensuring that your staff and patrons feel taken care of; what has been your strategy in maintaining this for the past five years?

My brother really taught me everything I know about hospitality. He was trained at Legal’s, but I also think that the Chinese cultural values around generosity and respect informed a lot of his approach to guests. We want our staff to feel like they have the agency to offer this kind of generosity all the time. After [Andy] stopped working in the business every day, we had to figure out how to institutionalize the “Andy” style of leadership. So, for example, in our point of sale we give our staff a $40 budget to spend on freebies for guests. Could be because we made a mistake, or because a guest got soaked in the rain, or because they couldn’t decide between the different kinds of dumplings and we want them to try all three. These are programmatic methods for supporting our hospitality philosophy.

Can you tell us more about Purple Table Reservations service?

Purple Table is all about signaling to guests that we understand that they may have special or non-standard needs or requests, and that it’s okay for them to ask. In fact, we want them to ask. It’s a communication channel that can be hard for guests to pave themselves. Training for staff can get specific depending on the particular need, but the general guidelines are: Don’t be a jerk, try to be helpful, treat the guest like they’re your family. We’ve made a couple layout changes and got the city of Boston to add an accessible parking space to our street, which previously had none. I grew up with a dad who had physical impairments through my teen years, and who then eventually developed Alzheimer’s. I remember the contrast between taking him to Legal’s, where my brother worked, and any other restaurant, where I would dine with constant anxiety that something bad or embarrassing or confusing might happen. I know that living with an impairment or as a caregiver can be incredibly isolating, especially when public spaces are unwelcoming. I think we as an industry can do so much better. Accessibility should be a baseline requirement of hospitality, not an added perk.

You are on several boards that feed Greater Boston’s hungry. How do you find the time for this and what compels you to do it?

The organizations I work with are all different pieces of the equitable-and-just-food-system puzzle. From supporting entrepreneurs to rescuing food to lobbying on Beacon Hill to creating jobs and food access, they all do incredible work. They’re also very understanding of my slightly crazy schedule. But for the most part, I don’t need to be at Mei Mei every day— we have purposefully built a business that is not highly technical and does not necessitate tremendous finesse. We want any staff person with any work background to be able to join the team and succeed. So that helps me make time. But I also do it because it creates balance for me, emotionally and spiritually, and helps me keep things in perspective. Mei Mei is the biggest thing in my world, but the world is much bigger than that. When I have a bad day at Mei Mei, it helps to remember that.

What do you do for relaxation?

I like to do the NY Times Crossword, and I love true crime podcasts.

What’s on your agenda in the coming year?

I’m hoping to open another location. Where, what concept, when—that’s all up in the air still.

Final question: How would you describe yourself to a blind person?

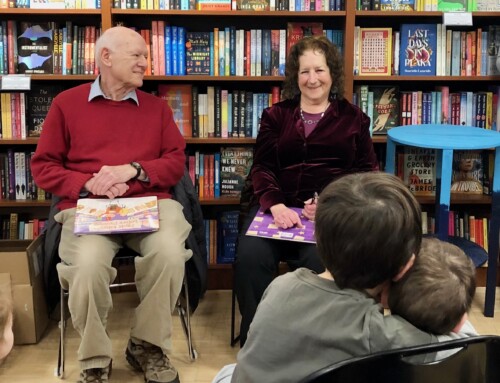

I smile a lot, using my whole face. I tend to gesticulate when I talk, and I almost always sit forward in my seat, leaning on my elbows or forearms. I wear Dansko clogs and like to wear jumpsuits/rompers/onesies, and pinroll tuck the legs. I have an offbeat haircut, a sort of mohawk that is long on top and shaved on both sides, which I always feel is the only cool thing about me.